Until September 19, 2021: MARIO PUCCINI, An Involuntary Van Gogh. Museo della Città, piazza del Luogo Pio, Livorno. Open Tuesday to Friday 10 am – 8 pm, Saturday and Sunday 10 am – 10 pm. Admission. €8.

Artists Mario Puccini and Vincent Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) have three things in common: both are Post-Impressionist painters born in the 19th century, each was temporarily committed to an insane asylum, and their subsequent works, often favoring similar subjects, burst with color.

Puccini (1869 – 1920) was a precocious talent who initially favored portraiture. Born in the Tuscan seaport of Livorno, Puccini’s artistic skill was recognized early, and he was sent to Florence’s Academy of Fine Arts at the age of 15, where he was influenced by the Tuscan “Macchiaioli” movement predominant at the time.

Comparable to the subsequent French Impressionism, works from this late 19th century movement, named for “macchie” used to describe loose brushstrokes, lending above all a sparkling quality. Composed of multiple layers, and a marked separation between the foreground and the background, canvases of this period capture the interplay of natural light.

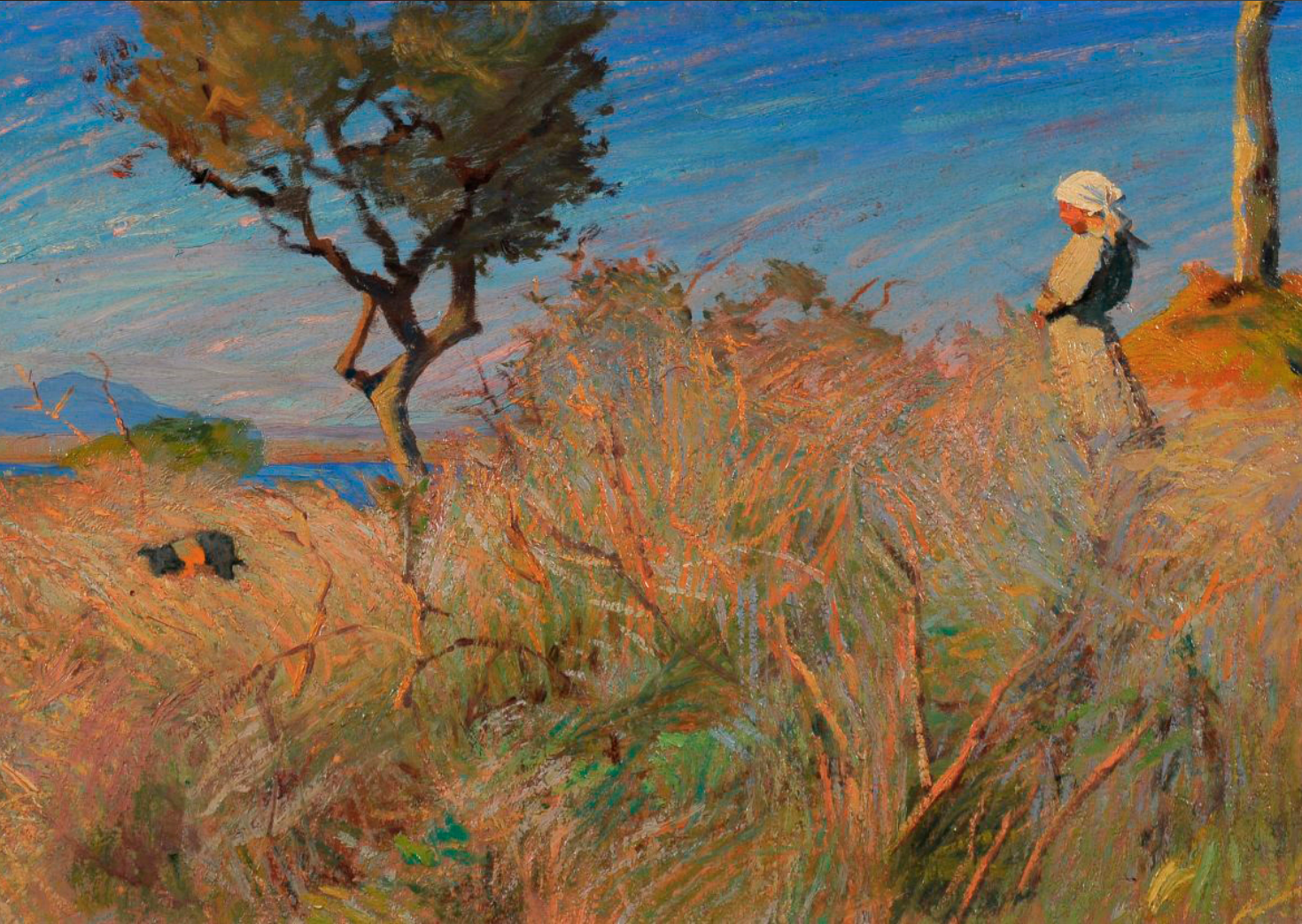

The exhibition displays paintings by Giovanni Fattori, including portraits of peasant women, showing the style Macchiaioli master that Puccini would absorb, an influence which radiated into the community of artists who followed him. Human figures are of little to no importance: while cattle and other details of nature are in realistic, crisp detail, people’s faces are blurred. When the movement’s collective focus shifted to landscapes, bodies become little more than small smudges on canvas, unless specifically requested.

Like Fattori, Puccini would depict bucolic countryside scenes of pastures and farm animals in his own unique way.

Very shortly after graduating from Florence’s Academy of Fine Arts, it is believed Puccini learned of his girlfriend’s infidelity, which sent him into a depression that was later diagnosed as mental illness, resulting in a six-year stay at psychiatric hospitals in Livorno and Siena.

Three self-portraits best explain his transformation during this period: in 1890, before diagnosis, his color palette is traditional, with a solid, neutral dark beige backdrop and tones of browns and blues. Twenty-five years later, he painted two others, both washed in light blue tones, with scraped and dashed lines behind his head.

This night and day difference characterized the rest of his career; for though most of Puccini’s work during his hospitalization was lost, everything after has been marked by his innovative use of color.

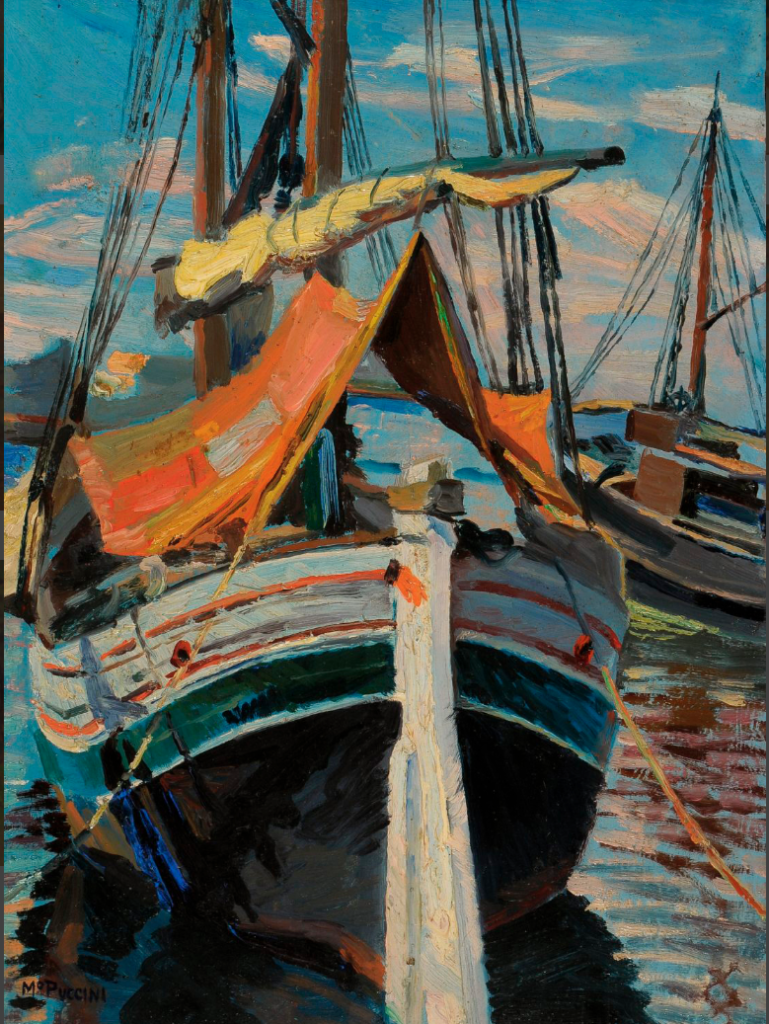

Dubbed the “Italian Van Gogh,” he modified Divisionism, a close cousin of Pointillism, to fit his own style, sweeping the canvas with longer, thicker brush strokes instead of the tiny dots. Chunky orange and yellow rectangles are stacked one on top of the next to form the sunset spilling out onto the water in many of his paintings featuring the port of Livorno, echoing Van Gogh’s boat scenes. Thanks to the intercession of fellow artist Oscar Ghiglia, Puccini had a chance to admire some of Van Gogh’s works–and those of Cézanne–in a private collection belonging to Gustavo Sforni.

This influence highlights his deviation from standard practices, favoring Divisionism, echoes of which are found in paintings by Van Gogh, who was influenced by this style and progressed beyond it in freer form of expression.

Puccini’s palette was also dependent on his location. While staying with his brother in Digne (France), sober navy blues and browns were most used, whereas in Italy, his landscapes exploded with intensely bright blues, crimsons, gold, and greens. He complemented this duality with different signatures: French pieces were signed “Pochein” instead of his Italian surname.

Though related to popular styles, the post-Macchiaioli movement and its host of artists linger in relative obscurity, neither celebrated nor discussed often today. Thanks to bright colors and use of light, in true Tuscan fashion, Puccini is a hidden gem. (bianca cockrell & rosanna cirigliano)