As those who recover from COVID-19 have shown to develop antibodies against the virus which could prevent another infection, immunologists hold hope for vaccine potential. Researchers studying the novel Coronavirus report some good news indicating the immune system’s response should protect against re-infection. Guido Silvestri, chief pathologist at Atlanta’s Emory University and known for his AIDS vaccine research, states this news is the “mega pill of optimism” and the best news since the pandemic broke out.

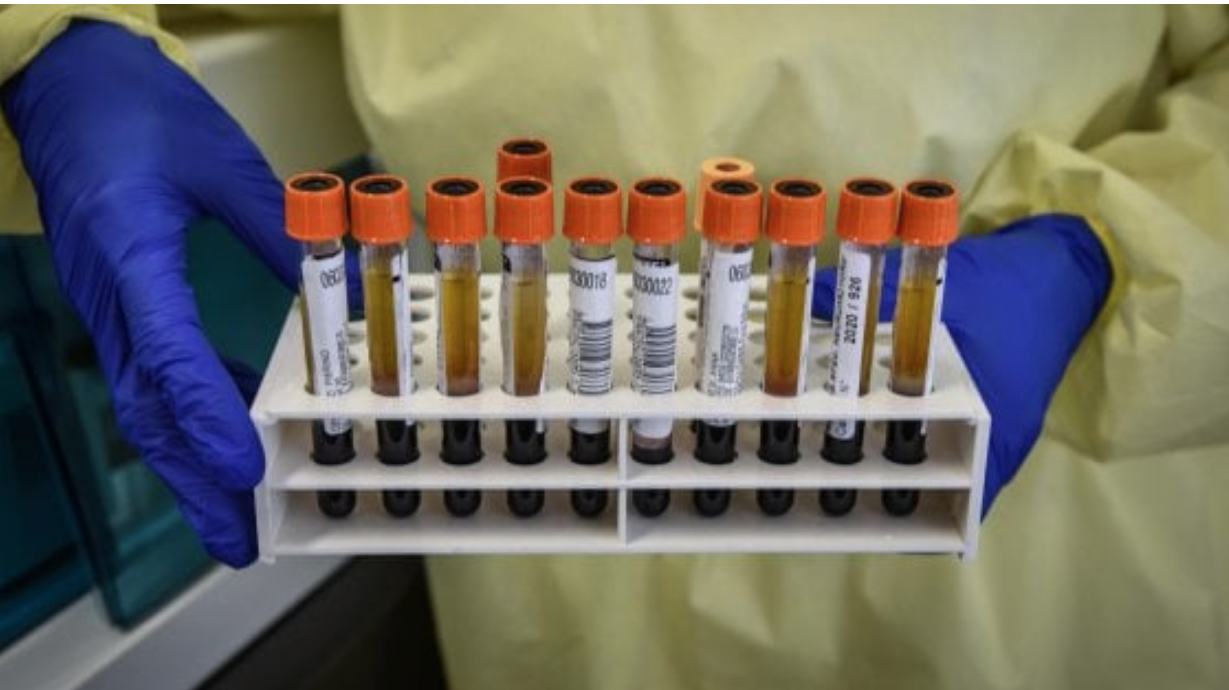

Currently Cisanello Hospital at the University of Pisa has begun conducting experimental therapy with plasma infusions donated by recovered COVID-19 patients who have developed antibodies to the deadly virus. On May 10, it was announced that their method will be the blueprint to be used in similar studies throughout Italy. The goal is to ascertain whether antibodies from healed donors can strengthen the ill patients’ immune systems. Two patients in Pisa, one in the Intensive Care Unit and one in the COVID-19 ward, have been administered the donated plasma. Dr. Francesco Menichetti, professor and director of the hospital’s infectious disease unit holds cautious optimism as the team monitors the effectiveness of the treatment.

A Chinese study, published in the journal Nature Medicine on April 29, 2020, reported that after 19 days of symptoms all 100% of 285 COVID-19 patients examined had developed antibodies specifically against the virus.

Antibodies, a blood protein produced by the immune system to stop intruders from harming the body, spring into action when a viral invader enters the body. The invaders, which are called antigens, can then be attacked by the antibodies and neutralized. After the infection is defeated, the antibodies remain in the body to protect again further attack by the same infection. Each antibody is able to protect against only one antigen. For example, a specific antibody is made to attack the chickenpox virus and only that particular antibody will deactivate the chickenpox virus.

Beginning with the initial trials in China in January, there are now experiments in progress in France, the Netherlands, the United States and Spain using convalescent plasma to treat infected persons. The process, complex because of the criteria of who can donate and who can receive the plasma, limits the amount of available plasma. Due to age and state of health restrictions, only 15-20% of potential donors are eligible.

As convalescent plasma treatment is currently undergoing trials, a consortium of labs and pharmaceutical companies is collaborating to develop a ‘cocktail’ of lab cloned immunoglobulin molecules designed to fight against the antigen responsible for COVID-19.

The use of this treatment has a historical precedent as during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, fatality rates were cut in half for patients who were treated with blood plasma compared to those who weren’t.

A Covid-19 vaccine is also currently being tested on 550 disease-free volunteers in an English clinic, the result of a joint collaboration between the researchers of Advent-Irbm in the Italian city of Pomezia (who had previously developed an effective vaccine for Ebola virus disease) and the Jenner Institute of Oxford University (see article here).

Meanwhile, on the island of Giglio off the coast of Tuscany, mass screening of the population was conducted to determine if and why residents might have a resistance to the Coronavirus. Even though the population has had exposure to the virus, with testing of 700 islanders, half of the island’s population, between April 29 and May 3, only one asymptomatic person tested positive. Earlier testing revealed that four individuals had tested positive, but all four were visiting from other areas. Two persons from Piacenza with a second home on the island, one boy from Lake Garda and another visitor from Paris were the four positive cases. They had contact with permanent residents, but apparently none contracted the virus.

Professor Paola Muti of the University of Milan supervised the serological testing and conducts ongoing research to answer why the population of the island might have resistance. One hypothesis, that the reduced rate of air pollution and particular geoclimatic conditions might reduce the viral load making the respiratory system stronger to enable combating the viral onslaught, has been proposed. The possibility that the genetics of the Gigliese population also cannot be excluded. (rita kungel)